9 ways racism impacts maternal health: A letter to my fellow Pilates teachers

Jun 07, 2020

(This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.)

Hello Beautiful Pilates teacher,

While the article below specifies Mother's Day, (and today is not mother's day on the calendar) the content is relevant to our country's current state; a deep necessity to better understand, and educate ourselves on racism, and how racism affects our pre and postnatal clients.

As teachers, it is our responsibility to do all we can to grow our awareness - in the ways we think, and behave.

I believe this is a good starting point to that education.

Sincerely, Alison Marsh - Founder of Pregnancy Pilates Impact

Roberta K. Timothy, York University, Canada

As we celebrate our moms and mommies this Mother’s Day, let us not forget that for some, motherhood is not an enjoyed privilege. For many Black, Indigenous and racialized women in Turtle Island (North America) and globally — motherhood is a fight for life.

The struggle for our maternal health and motherhood includes daily resistance against anti-Black racism, anti-indigeneity, sexism, classism and other forms of intersectional violence.

The health of Black pregnant women and mothers is a key issue being debated in the United States presidential 2020 campaigns especially by Sen. Kamala Harris and Sen. Elizabeth Warren. Recently, Harris introduced a resolution to raise awareness of the disproportionately high rates of pregnancy-related deaths among Black women.

Professional tennis player Serena Williams’ recent maternal health crisis demonstrated that Black women’s reproductive health can be jeopardized, suspect, dismissed and at risk of demise even for the very talented, wealthy and well-known.

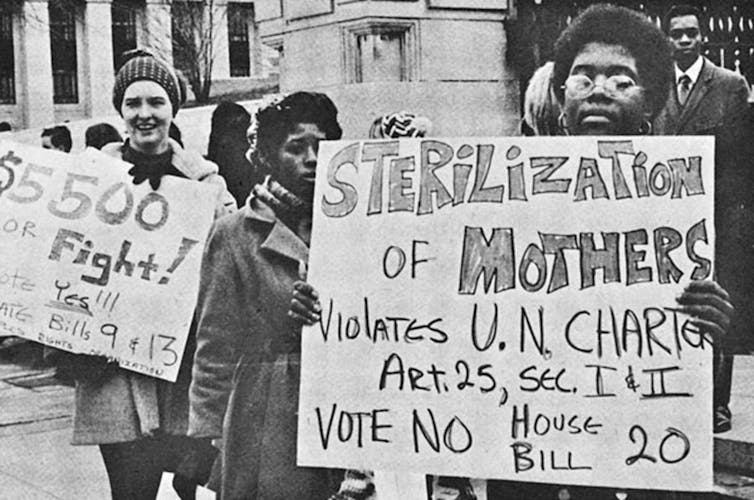

The historical exploitation of Black and Indigenous women through forced sterilization, rape, medical experimentation and other forms of torture through scientific racism, African enslavement and Indigenous genocide directly impacts maternal health outcomes today.

Read more: Raising children under suspicion and criminalization

This conversation is critical as we face recent fiscal cuts locally and globally to public health, education and anti-racism programs.

The World Health Organization defines maternal health as:

“…the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. While motherhood is often a positive and fulfilling experience, for too many women it is associated with suffering, ill-health and even death.”

Redefining maternal health is the goal of this conversation. We need to question our perceived notions of the “good mother,” supported through her pregnancy, encouraged to reproduce, usually identified as white, middle class and heterosexual. And we must question our ideas of the “bad mother” — generally not supported through her pregnancy, sometimes even discouraged to reproduce, usually identified as African/Black, Indigenous, racialized and poor.

Read more: U.S. support of formula over breastfeeding is a race issue

I briefly examine nine ways colonialism impedes maternal health using an integrated anti-oppression approach. I also look at some ways that we might resist these historical patterns.

Impact of maternal health inequities

State-sanctioned colonialism directly impacts the maternal health of Black, Indigenous and racialized communities as racist divisions continue to impede the likelihood of Black and brown babies’ and mother’s survival during our pregnancies.

Valid statistics coming from reputable sources support these facts. For example:

» Every day, approximately 830 women die globally from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth.

» In the United States, according to research published in 2010, Black pregnant women are three to four times more likely to die from complications compared to their white counterparts: 42 deaths per 100,000 live births among Black women versus 12 deaths per 100,000 live births among white women.

These statistics are helpful to describe an overall picture. However, missing from the stats are the context and impact of historical and current racism: that is, the impact of intersectional violence on maternal health.

Read more: What is intersectionality? All of who I am

But information about these contexts is difficult to garner. In Canada, maternal health statistics are not gathered based on race or indigeneity, despite the fact that racism directly impacts our health.

Anti-Black racism, intersectional violence and transgenerational trauma directly impact maternal health in the following ways:

-

Children: Many families live in fear of the state taking their children from them. This is a form of child incarceration, as practiced by the Children’s Aid Society. Another issue, the failure of the Canadian education system to retain Black youth, intensifies when the student is Black, young and pregnant.

-

Violence and neglect: Many live with fear based on their or others’ experiences of violence within the Canadian health system, including reproductive policing from health practitioners and lack of pre/post-natal mental health care. The loss of lives for Black women and Black children is a reality.

-

Criminalization: The increased criminalization of African women and their partners resulting in Black people being vastly overrepresented behind bars in Canada surely impacts health realities.

-

Precarious immigration status: Limited or non-existing health funding for immigrants, refugees and the undocumented can exacerbate existing health issues.

-

Housing and environment insecurity: Food, income and housing insecurity along with environmental apartheid can make lives unhealthier.

-

Daily stress of racism: The daily stressors of racism, stereotypes and racial profiling can create ongoing and persistent trauma which impacts psychological or physiological health and can block accessibility to appropriate health care.

-

Disability: Black folks living with disabilities have been historically overlooked.

-

Heteronormative practices: The complexity of the lives of Black and racialized LGBTQ and transgendered parents are often erased and many experience homophobic and transphobic violence including forced transvaginal exams during pregnancy and inappropriate comments while going for checkups or during birth.

-

Transgenerational trauma: Violence from mental anguish due to transnational trauma, known or felt (experienced), including trauma experienced in the lives of their parents and past and present community members, has an impact on the health of Black women. For example, there is a direct connection to the story of Mary Turner, a Black woman who was eight months pregnant and lynched in 1918, and how Black pregnant women feel the impact of racism in our bodies today.

Mother’s Day call to action

With these contexts in mind, any conversation on maternal health needs to recognize health disparities for Black, racialized and Indigenous women impacted by anti-Black racism, intersectional violence and transgenerational trauma and their impacts on motherhood, parenthood and our families.

These factors lead to anguish, sickness, harm and death.

Therefore, on this Mother’s Day, remember the political, social, environmental and spiritual fight for African/Black women, children and Indigenous communities to receive empowerment-centred healthcare services, treatment and support during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period from an anti-colonial framework.

We can work to counter this violence against Black pregnant women by conducting further research to provide information on how racism and other intersectional factors impact health.

We can also work to: reunify African diasporic families and communities; develop and maintain local and global health-centred advocacy spaces that support Black women and families to survive and thrive; decolonize our medical systems; challenge all forms of scientific racism and intersectional violence; and support African-centred maternal health spaces to heal.![]()

Roberta K. Timothy, Assistant Professor, Global Health, Ethics and Human Rights School of Health, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.